- Paul Krugman writes a popular article in New York Times Magazine on climate change economics.

- Nature reports on how Marine Reserves can be a ‘win–win’ for fish and fishermen. Our colleague Terry Hughes research is mentioned.

- Nature Reports Climate Change has several articles that relate to resilience to sea level rise. Mark Schrope describes coastal development in Florida (which combines a lack of planning with a lack of memory). Mason Inman reports on ecological engineering to adapt to sea level rise.

- An Economist special report on dealing with large volumes of data.

- Mathematican Steven Storgatz writes about analysis of social networks in New York Times in the Enemy of My Enemy.

Tag Archives: Paul Krugman

Economics as a complex systems science

An interesting interview of Paul Krugman by Edward Hugh is on A Fistful of Euros:

E.H. : The late Sir Karl Popper used to contrast what he regarded as science with ideologies like Marxism and Psychoanalysis, because there seemed to be no way whatever of consenually agreeing with their practitioners a series of simple tests which would enable their theories to be falsified. Some critics of neoclassical economics – including Popper’s heir Imre Lakatos – have expressed similar frustrations. Do you think we economists are, as a profession, up to the challenge of formulating testable hypotheses in such a way that the public at large might come to have more confidence in what we are up to, or are we a lost cause?

P.K.: I really don’t think that’s a helpful way to pose this question. Economics is about modeling complex systems, and as such the models are always less than fully accurate. What economists do need, however, is some demonstrated ability to get big things right. They had that after the Great Depression, when Keynesian economics clearly made sense of both the depression and the wartime recovery. But now the profession needs to get back on track.

Krugman on Keynes and Uncertainty

Paul Krugman reviews Keynes: The Return of the Master by Robert Skidelsky in the Observer. He writes:

…there’s an alternative interpretation of what Keynes was all about, one offered by Keynes himself in an article published in 1937, a year after The General Theory. Here, Keynes suggested that the core of his insight lay in the acknowledgement that there is uncertainty in the world – uncertainty that cannot be reduced to statistical probabilities, what the former US defence secretary Donald Rumsfeld called “unknown unknowns”. This irreducible uncertainty, he argued, lies behind panics and bouts of exuberance and primarily accounts for the instability of market economies.

In this book, Skidelsky puts himself in the camp of those who argue, in effect, that Keynes 1937, not Keynes 1936, is the man to listen to – that Keynesianism is, or should be, essentially about uncertainty and how it leads to economic instability. And from this he draws some radical conclusions.

Most strikingly, Skidelsky declares that the traditional division between microeconomics and macroeconomics, which is based on whether one focuses on individual markets or on the overall economy, is all wrong; macroeconomics should be defined as the field that studies those areas of economic life in which irreducible uncertainty, uncertainty that cannot be tamed with statistics, dominates. He goes so far as to call for a complete division of postgraduate studies: departments of macroeconomics should not even teach microeconomics, or vice versa, because macroeconomists must be protected “from the encroachment of the methods and habits of mind of microeconomics”.

How far should we be willing to follow Skidelsky in this? I think we must trust the biographer in his assessment of Keynes himself; Skidelsky argues persuasively that Keynes spent much of his life deeply focused upon, even obsessed with, the question of how one acts in the face of uncertainty, which is why Keynes 1937 comes closer to the essence of the great man’s own thinking.

That’s not the same thing, however, as saying that Keynes was right – even about his own contribution. Surely it’s possible to make the case for a less profound reconstruction of economics than Skidelsky advocates. I’d point out that behavioural economists, who drop the assumption of perfect rationality but don’t seem much concerned by the essential unknowability of the future, have done relatively well at making sense of this crisis; I’d also point out that current disputes over economic policy, above all about the usefulness of government spending to promote employment, seem to be primarily about Say’s Law – that is, Keynes 1936.

Paul Krugman on Betraying the Planet

In his New York Times column economist Paul Krugman strongly criticizes climate change denial in the US congress:

…we’re facing a clear and present danger to our way of life, perhaps even to civilization itself. How can anyone justify failing to act?

Well, sometimes even the most authoritative analyses get things wrong. And if dissenting opinion-makers and politicians based their dissent on hard work and hard thinking — if they had carefully studied the issue, consulted with experts and concluded that the overwhelming scientific consensus was misguided — they could at least claim to be acting responsibly.

But if you watched the debate on Friday, you didn’t see people who’ve thought hard about a crucial issue, and are trying to do the right thing. What you saw, instead, were people who show no sign of being interested in the truth. They don’t like the political and policy implications of climate change, so they’ve decided not to believe in it — and they’ll grab any argument, no matter how disreputable, that feeds their denial.

Indeed, if there was a defining moment in Friday’s debate, it was the declaration by Representative Paul Broun of Georgia that climate change is nothing but a “hoax” that has been “perpetrated out of the scientific community.” I’d call this a crazy conspiracy theory, but doing so would actually be unfair to crazy conspiracy theorists. After all, to believe that global warming is a hoax you have to believe in a vast cabal consisting of thousands of scientists — a cabal so powerful that it has managed to create false records on everything from global temperatures to Arctic sea ice.

Yet Mr. Broun’s declaration was met with applause.

Given this contempt for hard science, I’m almost reluctant to mention the deniers’ dishonesty on matters economic. But in addition to rejecting climate science, the opponents of the climate bill made a point of misrepresenting the results of studies of the bill’s economic impact, which all suggest that the cost will be relatively low.

Still, is it fair to call climate denial a form of treason? Isn’t it politics as usual?

Yes, it is — and that’s why it’s unforgivable.

Do you remember the days when Bush administration officials claimed that terrorism posed an “existential threat” to America, a threat in whose face normal rules no longer applied? That was hyperbole — but the existential threat from climate change is all too real.

Yet the deniers are choosing, willfully, to ignore that threat, placing future generations of Americans in grave danger, simply because it’s in their political interest to pretend that there’s nothing to worry about. If that’s not betrayal, I don’t know what is.

Assorted financial crisis news and analysis

The US radio show This American Life has an informative show on how non-transparent couplings between credit default swaps allowed caused the contagion that was critical to the financial crisis – Another Frightening Show About the Economy. You can listen to their show online or download an MP3 file.

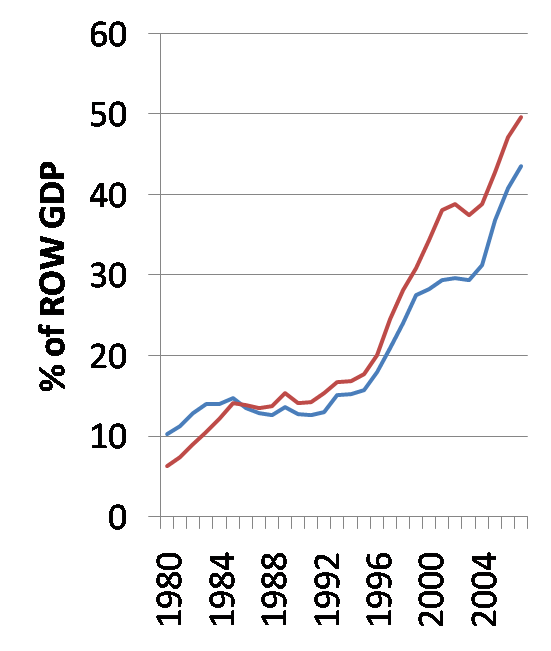

Also see economist Paul Krugman on the financial crisis here and with a longer analysis here. He also posts a revealing graph which shows the how the strength of the coupling between the US and the rest of the world’s (ROW) economies has increased over the past thirty years.

The US TV show 60 Minutes has a 12 min. segment on the “Shadow Financial System“. The segment charges the managers of investment banks with criminal incompetence.

Also, the New York Times, a critical look at the deregulation of financial markets under the US Federal Reserve chairmanship of Alan Greenspan. Taking Hard New Look at a Greenspan Legacy

“Not only have individual financial institutions become less vulnerable to shocks from underlying risk factors, but also the financial system as a whole has become more resilient.” — Alan Greenspan in 2004

And in the UK’s Financial Times, columnist Martin Wolf writes that is is now time for a comprehenisive plan to rescue the financial system:

As John Maynard Keynes is alleged to have said: “When the facts change, I change my mind. What do you do, sir?” I have changed my mind, as the panic has grown. Investors and lenders have moved from trusting anybody to trusting nobody. The fear driving today’s breakdown in financial markets is as exaggerated as the greed that drove the opposite behaviour a little while ago. But unjustified panic also causes devastation. It must be halted, not next week, but right now.

The time for a higgledy-piggledy, institution-by-institution and country-by-country approach is over. It took me a while – arguably, too long – to realise the full dangers. Maybe it was errors at the US Treasury, particularly the decision to let Lehman fail, that triggered today’s panic. So what should be done? In a word, “everything”. The affected economies account for more than half of global output. This makes the crisis much the most significant since the 1930s.

Paul Krugman on Resilience Economics

On Paul Krugman’s Blog he presents a graphical model of the current financial crisis in the US that implicitly discusses how the system lost resilience. He identifies leveraged investments as a slow variable which can lead to the creation of alternative regimes, the possibility for a shock to flip the system from one regime to another, and now possibly a new regime.

The other day I realized how much the Fed’s attempts to resolve the financial mess resemble sterilized foreign exchange intervention. That set me thinking about other parallels — and I realized how much the stories now being told about “systemic margin calls” and all that resemble the stories we all tried to tell about the Asian financial crisis of 1997-98. Leverage, balance sheet effects, self-reinforcing financial collapse — the details are different, but there are some clear common themes.

…Think of the demand for “securities” — lumping together all the stuff that’s in trouble, from subprime to Alt-A to corporate bonds, as if it were all the same. Ordinarily we’d think of a downward sloping demand curve. At a given point in time, there’s a fixed supply of these securities that has to be held by someone [Normal Situation]

But in the current situation, a lot of securities are held by market players who have leveraged themselves up. When prices fall beyond a certain point, they get calls from Mr. Margin, and have to sell off some of their holdings to meet those calls. The result can be a stretch of the demand curve that’s sloped the “wrong way”: falling prices actually reduce demand.

In this case, there are two equilibria, H and L. (there’s one in the middle, but it’s unstable) And this introduces the possibility of self-fulfilling panic: if something spooks the market, you can get a “systemic margin call” that causes the whole financial market to go to L, and causes a big, unnecessary price decline. [Highly leveraged investment]

Implicitly, Fed policy seems to be based on the view that if only they can restore confidence — with extra liquidity to the banks, Fed fund rate cuts, whatever — they can get us out of L and back to H. That’s the LTCM model: Rubin and Greenspan met a crisis with a rate cut and a show of confidence, and the whole thing went away.

But at this point a series of rate cuts and other stuff just hasn’t done the trick — which suggests that maybe there isn’t a high-price equilibrium out there at all. Maybe the underlying losses in housing and elsewhere are sufficiently large that the situation really looks like this [current situation?]

And in that case, the Fed can’t rescue the financial markets. All it — and the feds in general — can do is to try to limit the effects of financial crisis on the rest of the economy.