On PBS’s NewsHour, Paul Solman interviewed Nassim Nicholas Taleb and Benoit Mandelbrot about how strongly coupled systems can produce unpredictable turbulence. They strike very resilience oriented themes – narrow over-optimization leading to a loss of resilience.

PAUL SOLMAN: In the [Black Swan], Taleb wrote, “The increased concentration among banks seems to have the effect of making financial crises less likely. But when they happen, they are more global in scale and hit us very hard. True, we now have fewer failures, but, when they occur, I shiver at the thought.”

NASSIM NICHOLAS TALEB: The banking system, the way we have it, is a monstrous giant built on feet of clay. And if that topples, we’re gone.

Never in the history of the world have we faced so much complexity combined with so much incompetence and understanding of its properties.

PAUL SOLMAN: But there’s been complexity before. There has been overextension of credit before. We’ve had crashes in American history many times before. We’re a resilient system. Won’t we pull out of it?

NASSIM NICHOLAS TALEB: Let me tell you why it’s not like before. Look at what’s happening. The world is getting so fragile that a small shortage of oil — small — can lead to the price going from $25 to $150.

PAUL SOLMAN: A barrel.

NASSIM NICHOLAS TALEB: A barrel. A small excess demand in an agricultural product can lead to an explosion in price.

We live in a world that is way too complicated for our traditional economic structure. It’s not as resilient as it used to be. We don’t have slack. It’s over-optimized.

PAUL SOLMAN: What do you mean by “over-optimized”?

NASSIM NICHOLAS TALEB: Let me tell you what is happening in the ecology of the banking system. They’re swelling to large banks, OK, because it’s vastly more optimal to have one large bank than 10 small banks. It’s more efficient.

PAUL SOLMAN: Well, we’ve certainly seen the consolidation of the industry.

NASSIM NICHOLAS TALEB: Exactly. And that consolidation is what’s putting us at risk, because we are — when one bank, large bank makes a mistake, OK, it’s 10 times worse than a small bank making a mistake.

…

PAUL SOLMAN: So, getting back to your fundamental work and insight, this is a system that can become turbulent or is inherently turbulent, that doesn’t have enough of a buffer, and that’s the danger?BENOIT MANDELBROT: That is not well-understood. In fact, that is misunderstood for which tools have been developed which assume that changes are always very small.

If one of them comes, nothing bad happens. If several of them come together, very bad things have happened. And the theory does not take account of that, and the theory doesn’t take account of very large and sudden changes in anything.

The theory thinks that things move slowly, gradually, and can be corrected as they change, whereas, in fact, they may change extremely brutally.

NASSIM NICHOLAS TALEB: Now you understand why I’m worried. I hope I’m wrong. I wake up every morning — actually, I don’t wake up every morning now. I start to wake up at night the last couple of weeks hoping that I’m wrong, begging to be wrong.

I think that we may be experiencing something that is vastly worse than we think it is.

PAUL SOLMAN: And we think it’s pretty bad.

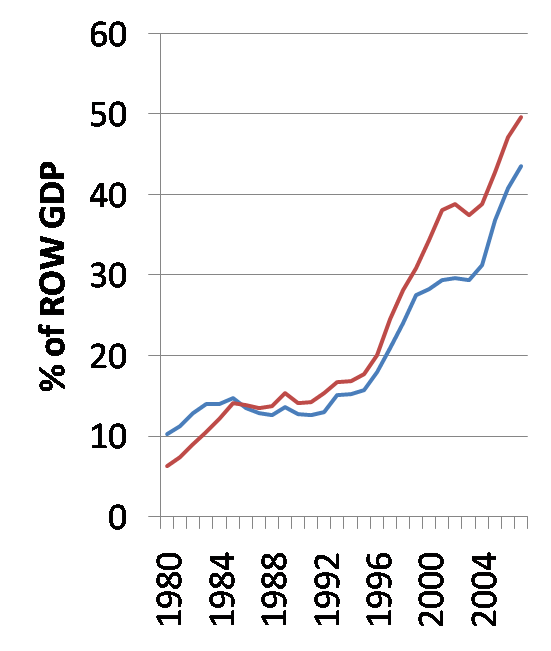

NASSIM NICHOLAS TALEB: It’s worse. Of all the books you read on globalization, they talk about efficiency, all that stuff. They don’t get the point. The network effect of that globalization, OK, means that a shock in the system can have much larger consequences.