Guest post by Simon West:

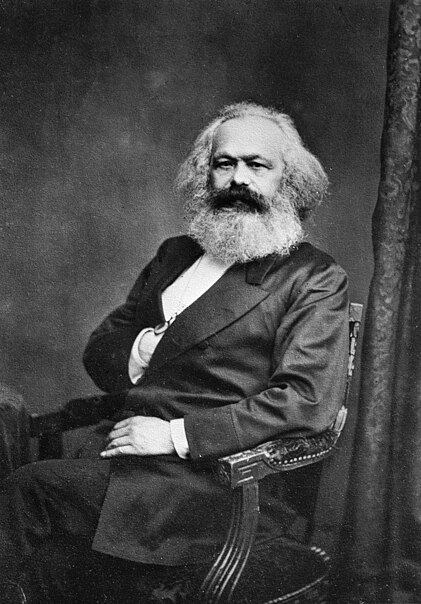

Karl Marx had modes of production, Emile Durkheim had collective consciousness; Max Weber wanted … nothing of this sort. He believed it was foolish to assign supra-individual entities a causal force in human history.

Nothing is more dangerous than the confusion of theory and history […]. This confusion expresses itself firstly in the belief that the “true” content and the essence of historical reality is portrayed in such theoretical constructs or secondly, in the use of these constructs as a procrustean bed into which history is to be forced or thirdly, in the hypostatization of such “ideas” as real “forces” and as a “true” reality which operates behind the passage of events and which works itself out in history” (Weber 2007 [1904], 214)

Weber marshaled two innovations to stay clear from the ‘fallacy of misplaced concreteness’ (Whitehead 2011 [1926]), i.e. mistaking the abstract for the concrete. First of all, he grounded his sociology in the German hermeneutic tradition of interpretation of interpersonal social interactions (‘verstehen’).

The hermeneutic tradition differentiates between the study of nature and the study of society, suggesting that, “while we can ‘explain’ natural occurrences in terms of the application of causal laws, human conduct is intrinsically meaningful, and has to be ‘interpreted’ or ‘understood’ in a way that has no counterpart in nature” (Giddens 2001 [1992]: ix). This distinction between the social and natural, captured in the concept of the “double hermeneutic” (i.e. the ‘object’ of the social sciences is also a ‘subject’) prominently developed by British sociologist Anthony Giddens, has remained a central problem for the study of human-nature interaction. The expanding range of approaches to human-nature interaction, including social-ecological systems, sustainability science, cultural geography, political ecology, anthropology, environmental humanities, etc. all address this dilemma in different ways.

Interestingly (particularly for social-ecological research), Weber did not think that a deep engagement with subjective human interpretation would make (social) science relativistic, or preclude causal explanation. Knowledge of the motives and rationalities that trigger people to act would, for Weber, still allow a causal explanation of human behaviour, but leave out any metaphysical extra-individual entities. He was strongly committed to the hermeneutic tradition, but at the same time endorsed the positivist ideal of a generalizing, parsimonious science. With this definition of sociology Weber elegantly overcame the two opposite positions in the so-called ‘methodenstreit’ (or ‘methods dispute’).

Aware of the ambitious standards that he set himself, he knew that it would often (if not always) be impossible to lay bare the multi-causal and complex interactions between the material and ideal worlds, the individual, the collective and the environment. He therefore – and this is Weber’s second major innovation – insisted that his analysis was not complete explanation, and only traced “one side of the causal chain” (Weber 2001 [1930]:125). He termed such ‘one-sided’ or ‘accentuated’ analysis ‘ideal-typical’, and the concepts it engaged ‘ideal-types’.

[…] the only way to avoid serious and foolish blunders requires a sharp, precise distinction between the logically comparative analysis of reality by ideal-types in the logical sense and the value-judgment of reality on the basis of ideals.” (Weber 2007 [1904], 215)

Weber’s most famous academic work, The Protestant Ethic and Spirit of Capitalism (1904), is a perfect example of an analysis through the use of ideal-types. The book traces the ideological basis (the spirit) of capitalism in the development of a protestant ethic in 15th century Europe. Weber was of course aware of the material origins of capitalism (his work has been described as a life-long debate with the ghost of Marx) but he in contrast focused on the ideas and rationale that produced capitalism. The book leaves implicit Marx’s legacy to identify the causal force of human interpretation in social-economic history. The book’s thesis is that the ‘capitalist spirit’ emerged from an austere ethic that Weber attributes to ascetic Protestantism, especially Calvinism, where beliefs in predestination, the idea of a ‘calling,’ and attribution of value to hard work established the pursuit of profit as inherently virtuous. Gradually the pursuit of profit transformed from being a means of salvation to becoming an end in and of itself; the protestant ethic became the capitalist spirit.

Weber’s most famous academic work, The Protestant Ethic and Spirit of Capitalism (1904), is a perfect example of an analysis through the use of ideal-types. The book traces the ideological basis (the spirit) of capitalism in the development of a protestant ethic in 15th century Europe. Weber was of course aware of the material origins of capitalism (his work has been described as a life-long debate with the ghost of Marx) but he in contrast focused on the ideas and rationale that produced capitalism. The book leaves implicit Marx’s legacy to identify the causal force of human interpretation in social-economic history. The book’s thesis is that the ‘capitalist spirit’ emerged from an austere ethic that Weber attributes to ascetic Protestantism, especially Calvinism, where beliefs in predestination, the idea of a ‘calling,’ and attribution of value to hard work established the pursuit of profit as inherently virtuous. Gradually the pursuit of profit transformed from being a means of salvation to becoming an end in and of itself; the protestant ethic became the capitalist spirit.

The Puritan wanted to work in a calling; we are forced to do so […]. This order is now bound to the technical and economic conditions of machine production which from day-to-day determine the lives of all the individuals who are born into this mechanism, not only those directly concerned with economic acquisition, with irresistible force. Perhaps it will so determine them until the last ton of fossilized coal is burnt.” (Weber 2001 [1930]: 123).

In direct connection to the above quote Weber invokes the image of an ‘iron cage’ as a metaphor for the stultifying rationalization of everyday life. According to his own ideal-typical typology of motivations of social action, a functional rationality (means-ends deliberation) gradually superseded and colonized alternative motivations, such as value rational, traditional and emotional motivations for action (Kalberg 1980). Characteristically, Weber did not see these motivations as operating exclusively and separately, but rather co-evolving in different arenas of human life at different speeds and scales.

Our class discussions revolved around the different ways that particular types of rationality shape human interaction with the environment today. As Giddens (2001 [1992]) points out, Weber’s work as a whole can be interpreted as a study of the divergent ways in which this rationalization of culture has taken place around the world – Weber published enormous and still influential texts on the major ‘world religions,’ including ancient Judaism, Hinduism and Buddhism.

Environmental historians (see for instance Robert Mark’s China: Its Environment and History or William Cronon’s Nature’s Metropolis) are increasingly unpacking the effects of these different forms of cultural rationalization on social-ecological interaction at the macro-scale.

The value of Weber’s ideas for social-ecological systems research is not easily overstated. Weber’s focus on inter-subjective interpretation influenced symbolic interactionists like Erving Goffman, who examined the meanings and frames of interpersonal interaction and understanding (Goffman 1974). In turn, Goffman’s work has prompted contemporary social theorists like Manuel De Landa to construct the social from networks and assemblages founded on personal interaction (De Landa 2006).

Weber’s ideas also resonate with recent work in cognitive science. George Lakoff, for instance, argues that individual ‘frames’ – mostly unconscious schemas including semantic roles, relations between roles, and relations to other frames – determine how we perceive and respond to environmental change (Lakoff 2010). While Lakoff does not cite Weber, they share sensitivity to the invidious and restrictive ways that subconscious frames, perhaps constitutive of an ‘ethic’ or ‘spirit,’ shape our everyday social, individual and even ecological experience.

Could Weber’s typology of rationality and associated forms of social action offer inspiration for thinking about social-ecological networks and SES modelling?

Max Weber completes the triumvirate of the classic ‘founders’ of sociology, and it is also with him that we reach the end of this course.

We hope this course can spark a wider exploration of the exciting theoretical options open to sustainability scholars.

Who are your classics?

On which shoulders do you stand?

The increasing willingness of sustainability scholars to excavate the classics to prompt new thinking of human-nature interactions may perhaps lead to a new generation of great theoretical synthesizers.

References

De Landa, 2006. A New Philosophy of Society: Assemblage Theory and Social Complexity. London: Continuum.

Giddens, A., 2001. Introduction. In: Weber, M. 2001 [1930].The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. London and New York: Routledge.

Goffman, E., 1974. Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of Experience. New York: Harper & Row.

Lakoff, G., 2010. Why it Matters How We Frame the Environment. Environmental Communication: A Journal of Nature and Culture 4(1): 70 – 81.

Kalberg, S., 1980. Max Weber’s Types of Rationality: Cornerstones for the Analysis of Rationalization in History. American Journal of Sociology 85(5): 1145 – 1179.

Weber, M. 2001 [1930].The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. London and New York: Routledge.

Weber, M. 2007 [1904]. Objectivity in social science. In: Calhoun et al. (eds.) Classical Sociological Theory. London: Blackwell.

Whitehead, A.N. 2011 [1926] Science and the modern world. Cambridge, University Press. Cambridge.