A recent paper by Yanhui Lu and others in Science (DOI: 10.1126/science.1187881) shows how ecological impacts of Bt cotton at the landscape level have lead to a surge in pests. In northern China, the cotton crop is 95% Bt cotton. The paper shows that Mirid bugs have increased both within cotton fields, but also in other crops grown in regions with large amounts of Bt cotton.

While the farmers who planted GMO cotton have benefited from it, the increase regional pest load has imposed a burden on other farmers who do not grow Bt cotton – a negative externality. This regional impact on other crops is shown in Figure 4 from their paper.

Association between mirid bug infestation levels in either cotton or key fruit crops, and Bt cotton planting proportion. The measure of mirid bug infestation was assigned a score ranging from 1 (no infestation) to 5 (extreme infestation).

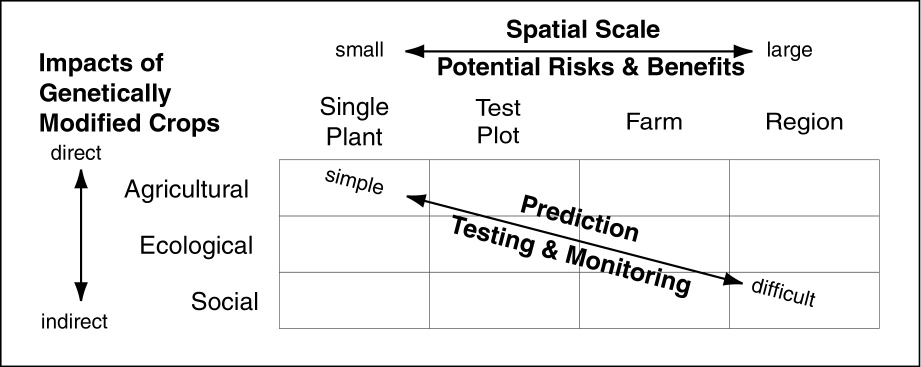

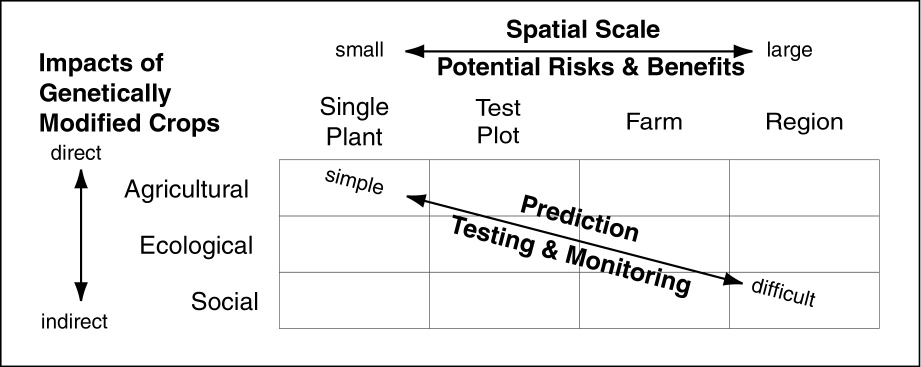

While this is the first paper, which I’m aware of, to demonstrate such landscape level impacts of GMOs on insect pests, this type of consequence of Bt GMO crops has been predicted for a long time. For example, ten years ago I argued in Conservation Ecology that risk assessment of GMO crops should include not only direct impacts, but indirect ecological impacts, as part of an adaptive risk assessment processes for GMO crops. Below is Figure 1 from that paper.

The direct and indirect effects of genetically modified crops interact with the scale at which they are grown to determine the difficulty of predicting, testing, and monitoring their potential impacts.

The Agricultural Biodiversity Weblog comments on the paper, and SciDev.net reports Bt cotton linked with surge in crop pest:

Their fifteen-year study surveyed a region of northern China where ten million small-scale farmers grow nearly three million hectares of Bt cotton, and 26 million hectares of other crops. It revealed widespread infestation with mirid bug (Heteroptera Miridae), which is destroying fruit, vegetable, cotton and cereal crops. And the rise of this pest correlated directly with Bt cotton planting.

Bt cotton is a genetically engineered strain, produced by the biotechnology company Monsanto. It makes its own insecticide which kills bollworm (Helicoverpa armigera), a common cotton pest that eats the crop’s product — the bolls. …

…

They watched the farms gradually become a source of mirid bug infestations, in parallel with the rise of Bt cotton. The bugs, initially regarded as occasional or minor pests, spread out to surrounding areas, “acquiring pest status” and infesting Chinese date, grape, apple peach and pear crops.

Before Bt cotton, the pesticides used to kill bollworm also controlled mirid bugs. Now, farmers are using more sprays to fight mirid bugs, said the scientists.

“Our work shows that a drop in insecticide use in Bt cotton fields leads to a reversal of the ecological role of cotton; from being a sink for mirid bugs in conventional systems to an actual source for these pests in Bt cotton growing systems,” …

Nature news reports:

The rise of mirids has driven Chinese farmers back to pesticides — they are currently using about two-thirds as much as they did before Bt cotton was introduced. As mirids develop resistance to the pesticides, Wu expects that farmers will soon spray as much as they ever did.

Two years ago, a study led by David Just, an economist at Cornell University at Ithaca, New York, concluded that the economic benefits of Bt cotton in China have eroded. The team attributed this to increased pesticide use to deal with secondary pests.

The conclusion was controversial, with critics of the study focusing on the relatively small sample size and use of economic modelling. Wu’s findings back up the earlier study, says David Andow, an entomologist at the University of Minnesota in St Paul.

“The finding reminds us yet again that genetic modified crops are not a magic bullet for pest control,” says Andow. “They have to be part of an integrated pest-management system to retain long-term benefits.”

Whenever a primary pest is targeted, other species are likely to rise in its place. For example, the boll weevil was once the main worldwide threat to cotton. As farmers sprayed pesticides against the weevils, bollworms developed resistance and rose to become the primary pest. Similarly, stink bugs have replaced bollworms as the primary pest in southeastern United States since Bt cotton was introduced.

…

Wu stresses, however, that pest control must keep sight of the whole ecosystem. “The impact of genetically modified crops must be assessed on the landscape level, taking into account the ecological input of different organisms,” he says. “This is the only way to ensure the sustainability of their application.”